The Leg Feint: A Metaphor for the Post-Colonial Educational System

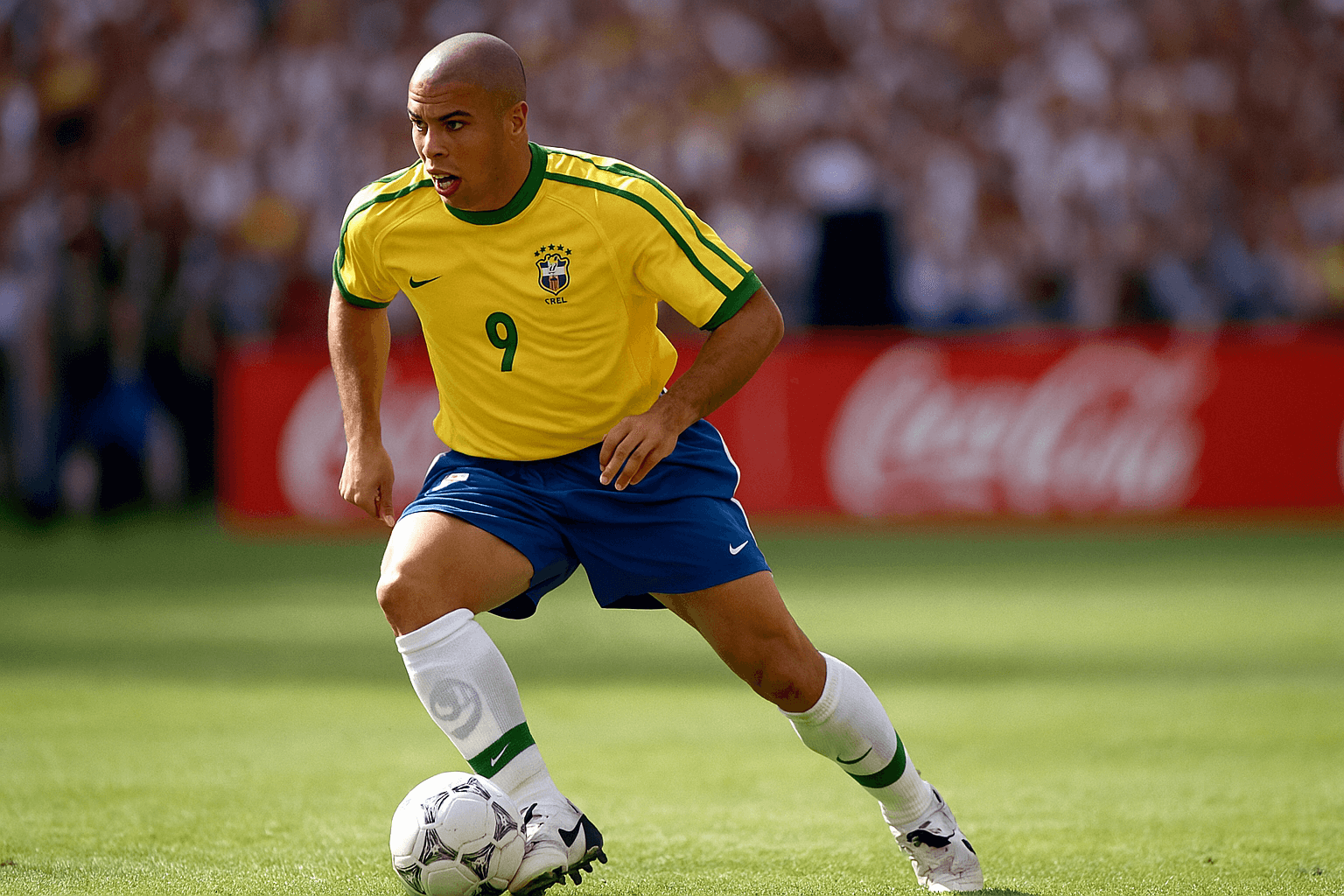

There are moments in life when the beauty of sport transcends mere entertainment to become a powerful metaphor for our social reality. Recently, I immersed myself in the video archives of a player who not only marked the history of football but also captured my personal imagination: Ronaldo Luiz Nazário de Lima, affectionately known as R9. This is not just an exercise in nostalgia—I had the privilege of watching him play live on television, feeling the thrill of each of his actions, marveling at his creative genius. Among all his technical gestures, one in particular caught my attention and led me to a profound reflection on our society: the leg feint.

The leg feint, in its apparent simplicity, conceals a fascinating strategic complexity. Imagine the scene: the player moves his leg over the ball, creating the illusion of a movement to the left, while his true objective is to go to the right. This gesture, sometimes repeated several times, is not just a simple feint—it is an art of distraction, a subtle manipulation of the opponent's perception. R9 perfected this technique to the point of making it his signature move, a maneuver that disoriented even the most seasoned defenders.

Colonial Education: An Institutionalized Leg Feint

This reflection on the leg feint led me to a troubling realization about the educational system in Africa, and more specifically in my country, the Democratic Republic of Congo. The parallel is striking: just as a defender can be trapped by a footballer's deceptive movement, we, as a nation, are victims of a masterful educational leg feint, inherited from the colonial system and perpetuated to this day. I still remember my secondary school years when I struggled to understand the geography of my own country. The reality was disconcerting: while the DRC is rich in strategic mineral resources, our education seemed deliberately designed to divert us from this reality. We spent hours studying in detail the geography of the European Union, memorizing capitals of distant countries, while our own territory—full of immense potential—remained a terra incognita.

This was not merely an oversight or pedagogical negligence—it was and remains a strategically effective leg feint. The school curricula are designed to distance us from fundamental truths about our identity and resources. Instead of instilling a deep understanding of the economic and social issues shaping our daily lives, they offer us a distorted view of the world around us.

Subtle Mechanisms of Cognitive Domination

The Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe, in his works on post-colonialism, emphasizes how contemporary systems of domination operate not through brute force but through more subtle mechanisms of control over consciousness. The educational system inherited from colonization is a perfect example. On the surface, it offers "general knowledge," an openness to the world; but in reality, it creates a profound form of cognitive alienation. Congolese students graduate knowing more about European economic issues than about their own country's development potential.

This mechanism is particularly insidious because it operates under the guise of "educational quality" and "international openness." As Joseph Ki-Zerbo explains in his work Educate or Perish, education in Africa must be rethought not as a simple transfer of knowledge but as an essential tool for liberation and endogenous development. Unfortunately, the current system continues to favor an approach that diverts us from our true developmental challenges—just as the leg feint distracts the defender from the attacker's true intention.

The Profound Consequences of Educational Diversion

The implications of this educational leg feint are vast and profound. We are training generations of young Congolese who, despite their diplomas, do not truly understand their country's strategic issues. How can they become actors in development if they do not master the mapping of national resources? If they do not understand potential value chains? If they do not grasp geopolitical issues related to strategic minerals? This situation creates a vicious circle where strategic ignorance facilitates ongoing exploitation by external actors.

Multinational companies and foreign countries can thus maintain their grip on our wealth—not through direct colonial force but through a more subtle form of domination: organized ignorance. As Samir Amin points out in his works on unequal development, this situation is not coincidental but rather the result of a system consciously put in place to keep our societies in a state of economic and intellectual inertia.

Towards a Radical Reinvention of Education

The solution to this problem cannot be limited to superficial reforms of the existing educational system. What we need is a complete reinvention of our approach to education. This transformation must begin with a comprehensive assessment of our resources and national potentials. It is not merely about cataloging our wealth; it is about understanding how these resources fit into a long-term vision for development.

Education must become a genuine national strategy aligned with a clearly defined societal project. This means developing programs that enable learners to understand not only what resources their country possesses but also how these resources can be transformed to create local added value. We need to train entrepreneurs, innovators, and thinkers who can imagine and implement solutions tailored to our realities.

The Imperative for Systemic Transformation

The necessary transformation goes far beyond simply improving "quality" in teaching. As Paulo Freire explains in his Pedagogy of the Oppressed, education must be an instrument for emancipation rather than domestication. This means fundamentally rethinking the content of our curricula, teacher training, and above all, the very purpose of our educational system.

This transformation must rest on a clear vision for national development over the next 50 to 100 years. What are our comparative advantages? How can we leverage them? What skills do we need to develop to achieve this? These are crucial questions that should guide the design of our educational programs—not imported models that do not correspond to our realities.

Conclusion: Beyond the Leg Feint

Just as a good defender learns to read the game and anticipate feints on the field, we must learn to recognize and counteract the leg feints that continue to handicap our development. Education should no longer be seen as a mechanism for distraction but as an empowering tool for development.

As Thomas Sankara said: “We must accept living African.” This means developing educational systems that respond to our needs, that value our resources, and that prepare our youth to tackle specific challenges on our continent. Only then can we transform this leg feint from domination into a determined race towards our own development.

Thus unfolds a new horizon where education becomes not only a vector for learning but also a powerful lever for building a future where every Congolese can fully thrive as a conscious and engaged actor serving the common good. This is where our true challenge lies: moving from passive acceptance to active engagement in constructing our collective destiny with pride and determination.